“Get up! The police want to talk to you!”

The sharp voices were raining from above while I was trying to regain my composure in a thirteen-meter-deep pit.

Still shaken by a conflict I engaged in, I was holding hands with a 5-year-old in a blue hood, my little human shield against reality. If only this nameless barefoot hobbit could have taken the magic ring out of his pocket and made us invisible!

I wanted to run. Far, far away! Away from an additional confrontation with a group of angry Chinese who wanted to beat the hell out of me. The situation escalated, and the police were about to get involved.

Suddenly, the imposing Church of St. George (Bete Giyorgis), carved out of Ethiopian mountain rock, felt more like a trap than an architectural wonder.

The bright skies above were an easy exit for birds. But for the wingless humans, there was no magical escape route. Without an invisibility cape, all paths out of this underground marvel of Orthodox Christian architecture led towards an ignited Asian bunch.

What seemed to have started as a relaxed Saturday morning of exploring the Lalibela churches, was quickly transforming into a tension-packed nightmare I just wanted to wake up from. Will I really have to go through police questioning now?

My decision to confront the Chinese was an instinctive one. It was certainly not a Christian thing to do. The locals probably followed Jesus better: If someone slaps you on one cheek, turn to them the other also (Luke 6:29).

At that moment, my threshold for tolerating bullies was rather low. When this Chinese group milked every single drop of Ethiopian politeness with extremely aggressive obsessive photography at an important religious site, I lost it. I wasn’t Jesus after all.

Photo shooting bullets

Years of traveling the world made me more aware of the impact our touristic self can have on local communities. The mere experience of a journey taught me to calm down the initial paparazzo impulse when approaching something exotic. We can and indeed should salvage and enjoy the moment without engaging in a photo-shooting mania.

Just because we are armed with photo cameras and not rifles, it doesn’t make them less of a weapon. Just because we are shooting pictures and not bullets, it doesn’t make us less responsible for the wounds we can inflict.

What I witnessed on that initially relaxed Saturday morning in Lalibela was a rape of privacy. Seeing it and not taking a stand would have made me an accomplice.

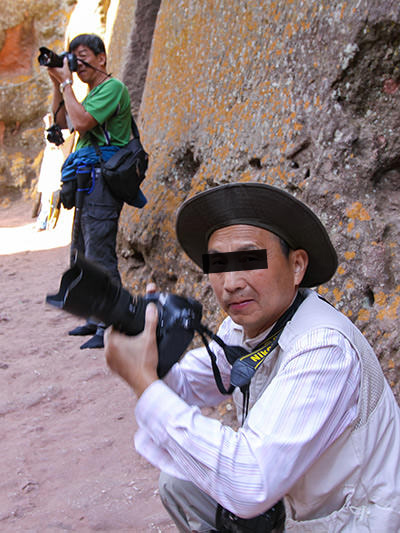

This group of eight Chinese tourists, heavily armed with a variety of camera bodies and lenses, were invading the Orthodox mass ceremony in a rather obstructive way. Making photo models out of regular churchgoers, and scenography out of medieval architecture, they were slaughtering the space with their Nikon machine guns.

Some of them even wore vests with the logo of the famous camera producer. They might have been here on a “serious” business.

Who knows, they could have even won some photography awards later with their extreme approach that was everything but documentary. They humiliated tradition, heritage, and silent tolerance of Ethiopians under their raping photography stampede.

Special places always seem to attract people with a serious problem of obsessive photography. Santorini sunset and Angkor Wat sunrise are just the most popular examples of touristic experiences ruined by the mania of claiming social media fame.

All Chinese are the same?

Since I was a child (and that was in the times of analog cameras, when one had to change the roll film after 24 or 36 shots!), the camera-clicking Asian tourist was engraved as one of the strongest race-based clichés in my memory.

Always in a group, always following the umbrella-carrying guide, and always making maximal use of a million photo opportunities. That cultural stereotype was later appropriated through movie scenes and the easiest solution of the mime games.

Even if I try to put this archetype aside, the idea of Chinese obsessive photography has constantly been reinforced during my travels. I knew that my entering the conflict in Lalibela was not just a response to the actions of these particular people. It was a reaction to the behavior of many before.

Being someone who utterly rejects reducing people to their nationality, already writing about the issue in this way made me question whether I am just perpetuating a stereotype.

I know Chinese persons who do not fit into this narrative. So clearly, I understand that all Chinese are not the same.

However, led by first-hand experience, I dare to think that there are peculiar, even when subtle, differences between, for instance, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese camera-equipped tourists.

Nothing can be generalized, but there seems to be a difference in the probability of a particular behavior being executed. More often than not, a Chinese tourist will embrace a certain level of pushiness and insensitivity towards the environment he/she tries to eternalize through instant photography.

When I read my writing, it does sound racist. So I did end up wondering: have I really, by defending one race in Lalibela, executed my latent inner racism?

The stereotype in the making

Before I dive deeper into what happened on that Saturday morning at one of the holiest sites in Africa, I feel I should share at least a few of the earlier episodes that surely shaped my newest response too.

1. No zen with karaoke

I have already written about my experience of staying at Hang Nga Guesthouse in Vietnam, also known as Crazy House Dalat. This peculiar hotel of strange architecture in Vietnam’s Central Highlands was more of an amusement park than an accommodation facility.

Hordes of tourists, many of them Chinese, were let into the hotel grounds to explore them, poke their cameras through the room doors, and peek through the windows. It was one of the strangest hotel experiences I’ve ever had.

In the Crazy House review, I didn’t mention that I also visited the Truc Lam Zen Monastery during my stay in Dalat.

On one side, Buddhist monks were trying to meditate while planting trees, and on the other, Chinese tourists laughed out loud, having wild picnics in the forest, practically real parties complete with gigantic sound systems and karaoke machines.

One had to see it to believe it. The word ‘zen’ in the name of the monastery lost all meaning.

2. Volcano party in the conflict zone

Danakil Depression in Ethiopia is the hottest place on Earth where people still live. Close to Eritrea, Erta Ale is an impressive active volcano. The real and political heat, the declared state of emergency, and even the killing of tourists made the climb to the volcano summit possible only during the night, with a military escort.

That didn’t stop young Chinese tourists from bursting into uncontrollable laughter, playing cheerful pop songs on a portable sound system, and generally disobeying the instructions by the soldiers.

They didn’t even follow the guide’s warning to mind where they step on, taking selfies from the unstable edge of the volcano rim. It seemed they didn’t care if tomorrow would come, or if they would join the faith of the German tourist coldly executed a few months earlier.

3. Drone attack on camels

Another group of nouveau riche Chinese tourists raised my eyebrows at Lake Assale, the Ethiopian salt flats where camels transport tons of the precious mineral every day.

Camel caravans are photogenic, and they attract many photographers to make their shots in the vastness of the desert.

A Chinese duo parked in their foldable armchairs and launched a large drone in the air. One would think a drone would be useful to get aerial footage of the caravan. But no, here it seemed to be just a substitute for laziness while following the animals on their route.

For one, flying close to the camels was disturbing them, as clearly they have never seen such a large mosquito in their lifetime. Secondly, this drone was practically in every shot of other photographers, completely erasing the naturality of the scene.

And these passionate aerial photographers were keen on shooting every single camel caravan passing by. I had to personally approach them and request to take into consideration everyone else trying to take photographs before the sunset, and only then did they realize that they were not alone in the world.

Possible explanations for Chinese obsessive photography

There are several possible interpretations for obsessive photography behavior among Chinese tourists.

The Chinese invasion of Bete Giyorgis

There have been many ‘inconsiderate Chinese photographer’ droplets filling up my patience cup over the years. So when I showed up for sunrise at Bete Giyorgis, one of the most impressive Lalibela churches, and a Chinese group quickly followed, I could almost anticipate their illogical movement patterns.

It was not crowded that Saturday morning, yet the Chinese quickly became unavoidable, entering every single frame of mine, and erasing any hope of authenticity one would hope to capture at such a site.

I gave up on exterior shots from above and followed the trench to get downstairs. The church mass was in progress. I didn’t want to obstruct, so I waited outside.

But the Chinese group quickly showed up at the entrance, and immediately I felt embarrassed to be a foreigner while trying to shush their noise down.

They took off their shoes (seemingly the only courteous act they knew of), and entered the church, ignoring the fact that even local women were standing outside.

After some time, I started to follow and observe their erratic behavior. They tried to climb the chairs in the church for a better shot and directed churchgoers to their liking.

They had no boundaries, getting into people’s faces, and annoying them persistently with bizarre photo demands.

Director’s in da house

The Chinese photographers manipulated an older woman like a puppet, in order for her to stand at a very particular place, in a very particular pose. She had to stop her prayers and stand by the door, staring outside, sunrays hitting her wrinkles perfectly, for that unique National-Geographic-style shot.

The photo monsters had this preconception of what they wanted to have in their memory cards at the end of the day. And they were not open to compromises.

They were instructing their “models” into holding palms together in prayer (I assume, that’s how a Chinese person imagines every Christian). I haven’t seen any Ethiopian engaging in that gesture on their own. When locals wanted me to photograph them, they were crossing their hands over their chests, forming “angel wings”. But authenticity does not sell, I guess.

At one moment, our tourists even stopped the priest from executing the ceremony. Seeing him bring a large pile of Bibles into the church, they didn’t take a shot in time, but it was something they didn’t want to miss. One jumped in front of the priest, blocking his path, and yelled: “Stop!” He just had to have that shot!

When the priest smiled at him, the photographer yelled: “Don’t smile!” The priest had to carry the Bibles with a serious face, he demanded. It was a bizarre director’s cut, and everyone had to ACT as told.

An altar server carrying a processional cross was practically abducted for the photo shoot, even if his body language was clearly stating he needed to join the mass.

But these Chinese photographers didn’t care much for people objecting. I saw them shooting even those churchgoers who were hiding behind their netela (Ethiopian cotton scarf). That’s when I realized: this was a school example of photo rape, no?

If you are interested in the history of objectifying other races for entertainment, read my review of the Basel Zoo! The popular Swiss institution is one of the last European zoos that was exhibiting black people as animals.

The price of surrender

In general, churchgoers complied with these demanding photographers’ commands, even if one could see they were not always doing it willingly.

If I could be so free to interpret this, I would say it was an act of conciliation. They were just ordinary believers attending the church mass, and we, the foreigners, were paying 50 USD (a fortune in Ethiopian terms) for the privilege to access the site. It’s hard to confront the demands of those who practically finance the church.

The possible interpretation for those who willingly participated could have also been the financial reimbursement for the photo they were hoping to get. It is not unusual for poor Ethiopians to ask for money in exchange for posing for a portrait.

My “colleague” with a hat was directing one older local to walk left and right, a gazillion times, until he made a perfect shot. At the end of a rather exploitative session, the old man said the only English word he knew of: “Money!” The Chinese guy pretended this was the only English word he didn’t understand.

He ignored the old man’s open palm, acting as if he doesn’t hear him, and continued shooting other motifs instead. I intervened and told the photographer that I believe this gentleman expects him to pay him for this modeling service. He still ignored both me and him.

Only when I came very close to him, did he open his wallet and hand over 5 birrs (9 cents) to the Ethiopian. It was the first small victory of mine in watching this exploitation unravel.

Fake one, take twelve: Fighting fire with fire

As I’ve learned in that Indonesian art gallery (check it out, it was Pipeaway’s most viral article), people do tend to act irrationally when confronted with a photo opportunity.

While the Chinese episode in Ethiopia did not have all the elements of the selfie mania I have witnessed on the bridge over the River Kwai in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, it still had elements of vanity too.

These photo aficionados from China were borrowing people’s netelas, entering their sleeping caves in the walls, and pretending to read the usurped Bibles for the photo.

Everything they were documenting that day in Lalibela was just fake. And they thought they could pay 5 Ethiopian bir for it.

Then this 5-year-old boy in a blue hood showed up. Later I would learn his name was Ashenafi Sisay. He politely approached one of the camera-clicking intruders and raised his hand for a greeting. But his handshake intention was ignored.

When you constantly exploit people for photographs, you might start confusing every raised hand for a financial demand you would prefer not to answer. This amiable boy just wanted to be a good Ethiopian, but he was invisible.

A young man, later I would learn his name was Sigey Melkame Bejena, was one of those churchgoers abducted for the Chinese photo needs. From afar, I saw he didn’t feel pleasant in the role, and I tried to use body language to signal to him that he WAS allowed to say ‘no’.

But even when Sigey raised his hand to protect himself from the lens, and demanded not to be photographed anymore, he was ignored.

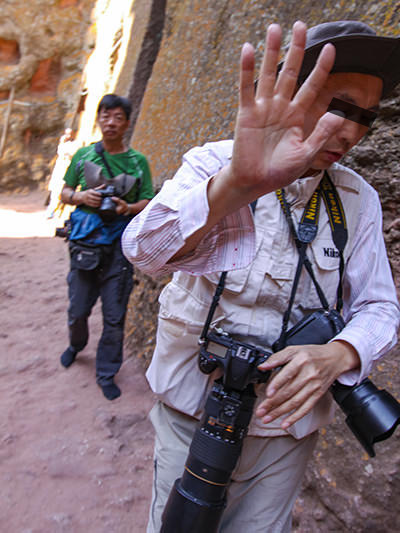

At that moment, I just couldn’t hold it anymore. The instinct took over my actions. I took my photo camera, approached the Chinese, and started to shoot THEM from up close!

Mad in China

They were infuriated. This simple performative gesture of mine was all it took to stop them from molesting the Ethiopians. And now they turned to me.

“No, no!”, the Chinese with a hat screamed. He raised his hands, protecting himself from my lens, the similar way that Sigey tried to say ‘no’ to him just moments ago. But there was a difference. Sigey was not on the edge of becoming violent.

“Delete! Delete!”, the photographer requested in a huff.

“Why would I delete it?”, I asked innocently. “I will not delete the photos. You are exotic to me!”

“Delete!!!”, he insisted.

“What seems to be the problem?”, I played dumb. “You are photographing them, I am photographing you. We are all just taking photographs!”

My subtle lecture on ethical behavior in photography did not seem to hit fertile ground. Which was logical. If the Chinese could have ever imagined what they were doing was wrong, they wouldn’t have been doing it in the first place. So it seemed as if I was trying to communicate with someone who obviously didn’t speak the same language.

As a matter of fact, the language of my peaceful protest against the photography violence was confronted by – body language. His hands which were previously abusing Ethiopians with a click of a button, now aggressively came after me.

“Do not touch me! I’ll call the police!”, was all I managed to threaten with at that moment. I’m really not a scuffle boy. The unnecessary noise already was making me upset.

All this commotion made Ethiopians gather around. I don’t speak Amharic, and they do not speak English, but I kind of understood that they were taking my side, trying to protect me.

A wreath of Ethiopians in white netelas was surrounding me, almost like Bilbo’s ring of invisibility. But my foe-friends still had a physical fight in their mind.

Winner Blessing in my hand

Sometimes, all it takes is to wait out. The Chinese exited the church through the trench. It seemed it was over, even if it wasn’t. But at Bete Giyorgis, this marvel of architecture, it was just me and the Ethiopians now.

After being forced to participate in a ridiculous photo session for an hour, the netela-covered strangers started approaching me. A simple “Thank you” was all I heard. They were all speaking these two English words.

The gratitude for what I thought was a plain normal human action was incredibly touching. After hearing so many thank yous in a row, my eyes filled with water.

I had my own set of troubles in adapting to Ethiopia (remember that African bus episode?), and it was a strange feeling of connection that overwhelmed me at this moment.

“Don’t cry”, the church guardian told me. “You are the winner!”

The 5-year-old, Ashenafi Sisay (his name translating as Winner Blessing, later I would learn), took my hand and held it strong. He released it only for me to put the shoes back on.

The security officer from above reminded me that there would be aftermath: “Come on up! The police need you!”

My new Ethiopian friends, Sigey and Ashenafi Sisay’s mother Mame Esayte Woldemariam, tried to explain to the security guy what had just happened. He still wanted me to come up to talk to the police.

One modest family in Indonesia also touched me deeply. It all started when Fathin Naufal reached out to me on Couchsurfing.

The art of disappearance

“Hurry up!”, he said, while I powerlessly pointed towards the 5-year-old’s hand slowly leading me out through the trench. There was not much space there, and this blue-hooded hobbit made sure not to let my hand go. Walking sideways like that seemed to last an eternity.

When finally outside, on the ground level, more and more netela-covered Ethiopians walked towards me to say two words only.

“Thank you!”

“Thank you!”

And then again: “Thank you!”

What was going on? Was I on live TV? There were not so many people witnessing the incident just a few minutes ago, but it seemed the news traveled fast. Quite a few Ethiopians wanted to approach me and make sure that I was okay.

One tour guide took me aside as he had heard that his Chinese tourists wanted to beat me up. He wanted to know what seemed to be the problem.

“I really don’t know”, I continued playing dumb. “There was no problem. We were all taking photographs, and then they suddenly got upset for some reason. But as long as I am concerned, there are no problems at all!”

The white tour van was parked at the entrance, at an unavoidable spot, and the Chinese were waiting for the conflict to resolve.

The 5-year-old and me, firmly holding hands and walking slowly like turtles, we passed by that van and went out of the complex with nobody ever noticing us. No police, no Chinese.

For that incredibly long moment, in the slowest escape ever, we seemed to be under an invisibility cloak.

Found in translation

Ashenafi’s mom invited me for buna, a coffee-making ceremony at her place. I don’t drink coffee, but I said: “Sure, I’d love to.”

It was a modest household in a slum, where no tourists ever walk through. Wildly built over Lalibela hills, this was an invisible home of real Ethiopia.

Poverty lived here, but the word ‘Happy’ printed out on a piece of paper and glued on their family home wall showed that it takes more to kill one’s spirit.

The 11-year-old daughter Tigist (meaning Patience) prepared coffee, offered me injera with shiro, and even washed my netela, bringing it back blindingly white and fragrant, ready for tomorrow’s mass.

Ashenafi was drawing and writing my name in Amharic, then taking photos with my camera and mobile phone.

Another daughter, Hanna (meaning Favored by God), studied textile engineering in Bahir Dar. Mame Esayte called her and proudly told her the church story.

This woman, dressed in a T-shirt with a ‘Lion King – Bilingual school’ imprint, had the face of a tired parent, exhausted by daily struggles, yet trying to provide the best life she could for her children.

“Do you eat bread?”, they asked me. I said yes, stupidly, thinking it was just a matter of curiosity. Soon, Tigist showed up at the door with freshly baked bread she just bought somewhere.

This humble yet invested single-parent family was doing everything they could to make my visit comfortable. It was warm and touching.

Mame Esayte Woldemariam would be calling my phone many times in the following weeks, and we would talk. Did I say that she didn’t speak English, and I knew no word of Amharic? Nevertheless, this woman felt deeply connected, enough to report on her daily life. At least, that’s what I thought she was telling me.

Unexpected miracles

Before I left their house on Saturday, these warm-hearted people gave me another present: a clay miniature of Bete Giyorgis church, and two printed photographs from their family album. That seemed like a precious thing to give away in the social reality they lived in. But they insisted I take their gift. I left them my own visa-style photo I accidentally had in my wallet.

We agreed to meet again the next day. After a mass in Bete Medhane Alem, the largest rock-hewn church in the world, we revisited the House of St. George. There were no more photography-obsessed visitors, and the world seemed different.

The church guardian, the one that proclaimed me a winner the day before, now guided me to see the treasures of the Church of Saint George that regular tourist visitors never get to see. Bete Giyorgis’s interior had hidden paintings of Saint George and the dragon behind the curtains, Lalibela’s chest with a special locking system, crosses on the wall…

I was able to take as many photographs as I liked and had people pose for me with no reciprocation expected.

The moral of the story, I guess, if my Chinese “colleagues” ever happen to read this, is that it doesn’t take much to reach other humans. The human approach can open up doors we never thought opening, and allow us, the photographers, to take images we never knew were there.

Something shifted in both me and the Ethiopians the days after the sad racial conflict at Bete Giyorgis. After being in the country for a month and a half, this was the first time I was walking down the street feeling truly accepted or blended in.

When there would be people stopping me, they would do it to say ‘welcome’, to ask how I was, or to compliment on ‘my wear’. I guess that bright, freshly washed netela did give me a Jesus-style glow.

Nobody was pulling my sleeve and asking for money. The (stereo)typical Ethiopia seemed to disappear.

I was wondering if prejudices and misconceptions are truly only in our heads. Or if the world can miraculously change once we contribute to the miracle.

Why the censoring of photos?

I am quite aware about the fact that internet can backfire. Hidden behind our screens, we can direct our frustrations towards people instead of behaviors (remember how that selfie girl became an easy target?). In order to minimize the danger of perpetual violence, I have decided to partially protect the identity of the main actor of this obsessive photography story. Until someone informs me that he has actually won some photography award for his "documentary work" in Lalibela, I believe his face will be less relevant than his actions. For the sake of improving our conversations with other people and cultures, I would prefer if we could focus on phenomena instead of trampling someone who is already down.

What are your views on Chinese obsessive photography? Do you believe it exists? Please comment below!

If you like this article, pin it for later!

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means if you click on them and make a purchase, Pipeaway might make a small commission, at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our work!