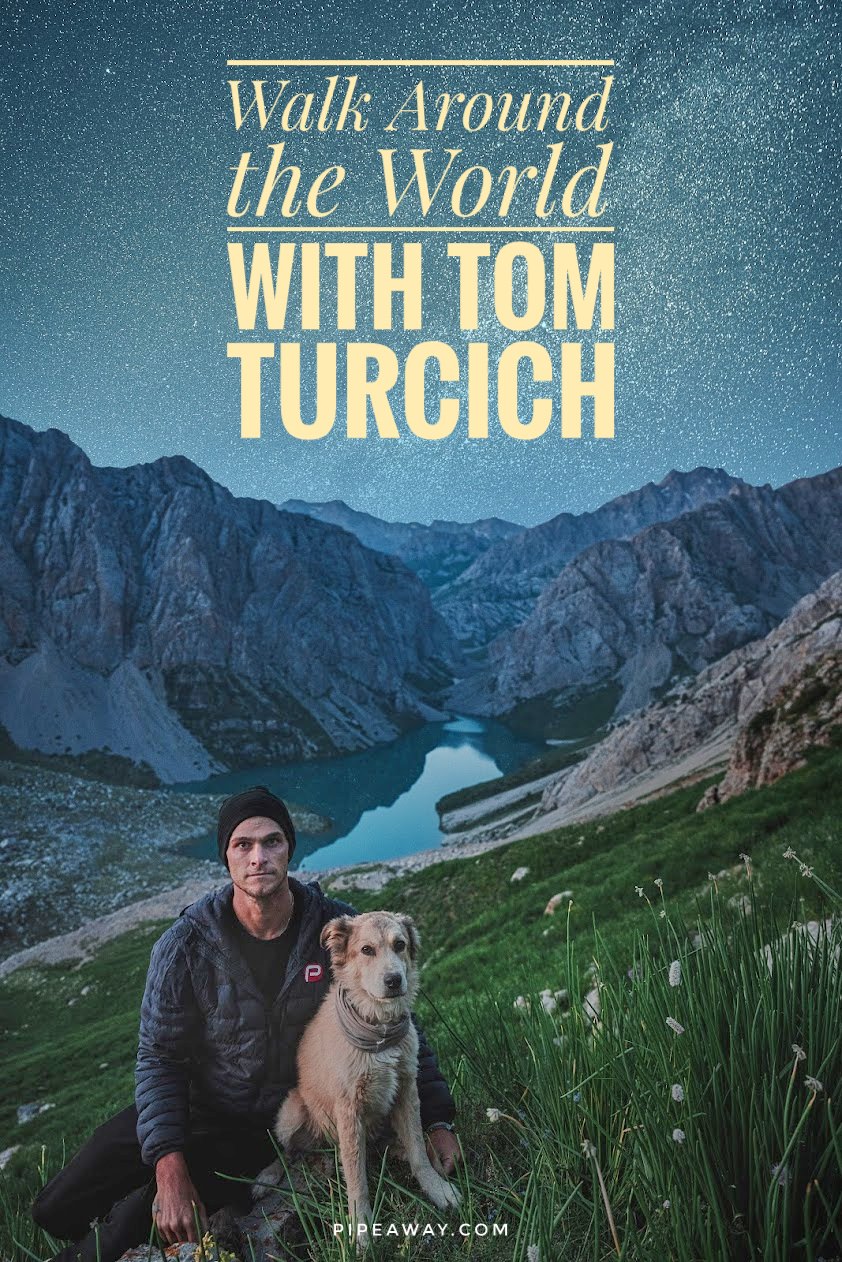

When one takes a dog for a longer walk, it usually means getting outside for a couple of hours. But when Tom Turcich (34) adopted a dog in an animal shelter back in 2015, he took Savannah, then a puppy, for a seven-year-long stroll – the walk around the world.

After covering 45 thousand kilometers on foot, the adventurer Tom Turcich became the tenth person to circumnavigate the globe this way, setting foot on six continents, and wearing out 45 pairs of shoes in the process. Savannah became the first dog to conquer 38 countries on paws alone.

Tom Turcich’s legs took a well-deserved break, but challenges didn’t end when the walk around the world did

Tom left his parents’ home in New Jersey a day before his 26th birthday and returned as a grown man that matured beyond just accomplishing a remarkable feat. The epic journey enabled him to explore his own and other people’s heritage and learn valuable lessons about life.

He already knew how fragile life was. When he was 17, his childhood friend Anne Marie Lynch died in a jetski accident, unleashing a whirlpool of emotions. Even the best ones among us can disappear tomorrow, Tom saw, and this essentially became a first push towards the World Walk.

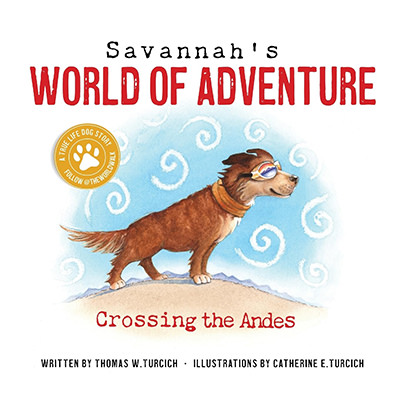

A year has passed since Tom’s legs took a well-deserved break, but his mind continues racing. I caught up with him in Cincinnati, where he just settled with his girlfriend Bonnie. Between working on writing his memoir (hitting shelves in spring 2024), self-publishing his children’s book “Savannah’s World of Adventure”, juggling speaking engagements, and unpacking the boxes from moving, he revealed that challenges didn’t end when the walk around the world did.

Transitioning back to a non-walking life has meant relearning what he knew about living among people, rewaking obsessive thoughts on mortality, and embarking on an ongoing quest for identity and purpose.

Tracing the Turcich roots

Becoming the tenth person to walk the world made you an instant media sensation. Through watching your public appearances, I noticed numerous journalists struggling with the pronunciation of your last name as [Toor-seech], [Toor-kitch], or [Toor-chik], never hitting the Croatian version [Toor-cheech]… I wonder how you pronounce the name of your Croatian ancestors, and did it change after visiting their homeland?

Here, it’s [Toor-seech]. It was awesome to go to the island of Krk and see the little village of Turčić. I have one of my ancestors in Ireland too, but in Croatia, it just felt it was on another level, being able to go and see the town, to see the headstone with my last name on it, and meet my cousins there. And you’re like, ‘No wonder my great grandfather left Krk because it’s all just rock. This would be insane to live in the 1800s, that’s crazy.’

A lot of my aunts stayed in contact with cousins and family everywhere. There’s a good Turcich network! They would just tell me: “This is your cousin, Milijana, go stay with her! And then she’ll introduce you to more cousins, and you’ll meet these cousins, and they’ll show you these cousins!” It was just getting contacts of a few of them, and then me bouncing around.

Who is Tom Turcich after the World Walk?

It’s been a year now since you finished your seven-year-long quest for meaning by walking around the world. After being constantly on the move for so long, and now exploring the side of you that doesn’t have that always-present mission in the spotlight, what have you learned about yourself? Can you now answer better: Who is Tom Turcich?

Man, it’s difficult to answer that question now! Before it would have been very easy, I think. My whole purpose was wrapped up in the World Walk.

Like you said, every day I’d wake up and have that purpose of getting up and walking, it was very simple. Just by doing that one simple thing, I saw the world, I had new experiences, I met new people, I tried new food, and I didn’t have to really do anything. I just had to get up and walk, and then find the place to sleep, and get some water and food for me and Savannah.

And now, it’s definitely challenging. I don’t know, it’s a tough question to answer honestly. I wake up now and the days are just very open, in a way they didn’t use to be. I go: I could do this, I could do this, I could do this… I think I’m still figuring out who I am after the walk. And I think that’s hopefully to be expected; after having such a clear purpose for so long, I’m in search of a new purpose, of something new that would drive me. But yeah, it’s tough to say, I’m in a gray zone.

Boredom and crisis beyond the finish line

After you finished that journey that lasted 1861 days and walked through the finish line in Haddon Township, things seem to have changed. As a photographer, you barely posted five posts on Instagram in the past year. Did you feel as if your life became boring, did you enter an existential crisis, or were you just bothered by some new questions?

I would say all of them. Definitely boring, definitely an existential crisis…

Life on the road is really fulfilling, and there’s just so much stimulation and challenge to it. I’m glad it’s over, as it’s difficult. But with that difficulty comes a lot of richness.

The World Walk was my answer to my mortality, and now that it’s over, I find myself thinking about death a lotTom Turcich

Now that life is a little easier, I can shower every day, I can lie in bed, I can make a coffee whenever I want to make a coffee, there’s this sort of boredom in a certain way. Because I don’t have that sense of discovery that I used to have.

And then there’s definitely an existential crisis because the World Walk was my answer to my mortality. And now that I don’t have that anymore, and I am not waking up outside, in the tent, or in a new place, I really find myself thinking about death a lot. And what I need to do to make my life meaningful to me, and worthwhile.

So there’s a lot of questioning. In a certain way, there is a lot of boredom. Yes, I don’t have that strong sense of purpose. At the same time, I am very grateful to not go through all of that.

When I was in Croatia, it was during the heat wave, and it was so insanely hot when I was out walking. I don’t miss that. But I also do miss walking through that heat in the morning and just dying, and then I’d get to these little beaches all along the water there, and take a 3-hour break, and I’d just swim for an hour. That was amazing.

But yeah, it’s been a challenging transition for sure.

From wanderer to wonderer

Maybe everyone expects you’d mature through this journey, and I’m sure your parents would say you’re not a boy anymore. But do you also feel as if you went back somehow, to feeling lost like a teenager? You passed the finish line, but you are again at the beginning in a way…

Yeah, definitely. I am such an entirely different person than I was when I started. The growth happens so slowly, you don’t even notice it’s happening after a while. Just like my understanding of the world, my understanding of myself is so far beyond what it was when I began.

But as you said, in a certain way, I do feel that I’m behind strangely. I was living such a different life, and I come and see people having their careers, they go to kickboxing or other classes, and they have all these friends or the wardrobe… They just know what they are doing in this one place, and I didn’t have any of that.

I’m feeling more and more settled by the day and figuring it out again. But I remember when I stopped and moved to Seattle, I just had so much time on my hands. The world wasn’t coming at me as it did when I was walking. And I realized, ‘Oh, I have to go out and sign up for classes, or go to the tennis court and play tennis.’ Like, I had to do these things. Whereas when I was walking, I would just walk and everything would come at me.

It’s difficult, it’s a change. But you know, after a year, it’s getting easier and easier, I would say.

Tom Turcich’s journey through loneliness

For seven years of your World Walk, you were living a repeating, but slow-tempo life. As you said, after you returned, you saw your social circles had moved on rather quickly. And maybe they even live rather quickly, rushed by their job duties, families, activities, things to do… Did you feel alone?

A little bit, yeah. When it ended, I was at my parents’ house in New Jersey for three months. I was really in the afterglow of having finished. I was seeing all my friends and family. I could just do nothing and be totally satisfied.

When I was walking, I never felt alone. But as soon as I would stop in a city, I would feel lonelyTom Turcich

Then I moved to Seattle, to be with my girlfriend Bonnie. It was great being there and I moved there for a reason, but also I only knew two people out there, and she was off to medical school. There was definitely little more isolation.

And again, a part of it was that I just didn’t know what to do with my time. How do I fill my days?

A similar thing was happening when I was walking. On the days I was walking, I would never feel alone. But when I would stop in the city and didn’t know anyone, that’s when I would feel lonely. Because you see all these people walking and doing stuff, and you think ‘I’ll just gonna sit here and do people-watching’. You really feel you don’t have any of these connections.

It felt the same way in Seattle for a little while. But eventually, I got my group, got into a little more rhythm, found ways to spend my day, and felt a little more assured.

Also, I loved being outside, and I was in an apartment. You had to go to some public space to be outside, and I just wanted to sit out. Now, I’m in a house and I can sit out on the front porch. I just need to be able to sit outside somewhere, on my own.

There are environment-friendly ways to travel to the other side of the world without necessarily involving walking. Meet the British family that decided to travel slowly to Australia!

Transient connections

You speak about loneliness in the crowd. Even for the social connections you did make on the road, you had to take into account that you would be saying ‘goodbye’ the next day. It’s a social life that’s always ending, right?

I got really sick with a bacterial infection after South America. I came back, and I was walking in Europe, and it was difficult because I had been in a lot of pain over the seven months before from the infection.

When I got to Valencia in Spain, I stopped for a month and a half to get a Spanish visa. And I met this girl there, and I just wanted some connection, some permanence, and had to leave it.

Then, when I was walking Morrocco and Algeria, I was meeting these great people, and again I wanted to stay in some of these places, and I wanted to have this deep connection.

I really just had to accept this was the deal I made, this is a part of the World Walk. You can’t stay in one place. Definitely in that section of the world, probably from Spain to Algeria, it was really me trying to come to terms that it’s not the time yet to have these connections.

I would obsessively think about what my house was gonna be like in the future, I was really nesting, I couldn’t wait to have my place and have people around. But at the same time, just over and over again, I’m just leaving and go ‘You just can have this’.

In Azerbaijan, I stayed for six months because of Covid. I lived with a Swiss girl, I pretended normalcy. Even if the world was very not normal, for me it felt normal, I was in an apartment, buying groceries, and so on.

Then in Turkey, I walked around and stopped in Kaş, on the south coast. It was one of the few places where I could keep walking. I stayed for three months, I had friends, and everyone was in the same situation, it was a pandemic hide-out. And I had those connections. Having those made me really appreciate and long for being in one place and having connections.

When I left again in Uzbekistan and Kyrgistan, and then I walked across the US, I was also really exhausted from leaving people over and over and over again. I’ve just done it for so long, and I was really looking forward to not doing that after six years.

A man from Canada also didn't let the pandemic stop him from his trip around the world. Bert terHart became the ninth person to sail around the globe alone, using only celestial navigation!

Love on the road

So you broke two hearts while on the road?

Yeah, well, I think in Valencia it was more of a fling and I was in a bad state emotionally and just wanted the connection. But in Azerbaijan, it was a girlfriend.

Did you break these connections because of the walk, or were you considering maybe breaking the walk to continue the relationships?

No, that was never gonna stop the World Walk. That was always in the back of my head, and I was always upfront about it: “This is what I’m doing.” And to myself as well. That’s what also made it difficult, that I knew nothing was permanent or could be lasting.

So it’s like a one-night stand, but it could last for a month maybe, but not longer…

Yeah, exactly.

How did Bonnie and you meet?

We met on the road, in Washington State, I was halfway across Washington, and she was doing a rotation in a little town called Omak. Got on Tinder, she was on Tinder, and we kind of hit it off. I stayed with her for a couple of days, on Labor Day weekend, and she followed me. She saw me in Washington, then in Idaho, in Wyoming. She visited me in Colorado on Christmas, and Pittsburgh as well.

Did she walk with you, or just followed where you are?

She walked a little bit, here and there, not like a full day and night.

Do you know about Christian Lewis who started a solo quest of walking Britain’s coastline, and ended up not only with a dog, but also now a partner, and a baby, all doing the walk? I’m not pushing this scenario, but do you have family plans?

Maybe. You know, I’m still trying to fill up my wardrobe and sign up for classes. Maybe in a couple of years, we’ll see. The dogs are enough responsibility for now.

Canine culture

What country loves dogs the most?

Oh, probably America. Americans are crazy about their dogs. They are like our kids. I don’t think there’s anywhere else as extreme as in the US.

I would say Turkey is pretty good about their dogs too, in a very different way. Dogs are not generally brought inside, but people are very respectful of the dogs. They are fed, and spayed/neutered, they are just left to roam, which is really nice in a certain way.

There were a lot of places that were very receptive to Savannah. They really loved her in Uzbekistan. Because it was kind of an anomaly. Maybe every once in a while, someone would have a dog, and it was so strange for them that I would be walking around with this dog on a leash. Whenever they met Savannah, they would love her. Uzbekistan was really friendly, more out of curiosity.

And which country do dogs love the most, according to Savannah?

Kyrgistan, for sure. We were just up in the mountains, with the horse and the guide. So she was off leash basically all the time, and just running around the mountains, on the grass, chasing yaks, goats, and sheep. She was in paradise.

Savannah’s journey from trauma to trust

As it was the only life she knew of, do you feel she grew into a different type of dog? When she was meeting other dogs, used to their leashes, courtyards, and neighborhoods – what were their encounters like?

Yeah, very different life. During the first two years in Central and Southern America, she was attacked by other dogs a lot. There are a lot of dogs that are beaten or just not treated with any love, but just there to protect someone’s property, and they are given some scraps. So the first two years, she had a lot of trauma. She didn’t trust other dogs.

When we got to the US, and I was getting her paperwork to get into Europe, we would go to this dog park, and she would just stand on the side, and watch the other dogs, and not really know how to play. It wasn’t until a month in or so, when we would get to park and she would be so excited. Because she was like ‘Oh, I know I can trust these dogs, and they are not going to attack me’. And now she is so friendly.

She still has some weird little quirks. When I was camped out somewhere, and I walked away, maybe to go to the bathroom, or just go explore somewhere not too far away, I’d leave the tent set up. And as soon as I would turn around, she would race back to the tent to go see if anyone was there, to protect it. She still has that, when we walk. As soon as we turn around, she’s pulling as hard as she can, to get back to the house. And if I’d let her off leash, she would just run home to protect it. So she has a few little quirks from the road, but she is on the sofa right now, sleeping, so I think she is pretty happy about that too.

Bedtime choices

On the road, did she prefer sleeping on the grass outside or in the tent?

For the first two years, it was always outside. She never came into the tent. Even if I wanted her to come inside. Even if it would rain, she would sleep in the vestibule, the little outside area.

But then we spent a month in Montevideo, Uruguay, and then two months at home, to get her paperwork to get her into Europe. I think after that she was like ‘I’m just gonna be in the tent, that’s nice too, to be inside’. Then it was quite often in the tent.

After sleeping on hard surfaces for so long yourself, how do you prefer to sleep today?

Sleeping outside is definitely nice. I sleep really well outside.

I spoke at this camp to a graduating class of seniors, and I was sleeping in the cabin. Just having sounds of nature and a little breeze coming in, I slept so well. Even if the mattress was terrible, I didn’t even have a pillow, I was in a sleeping bag, but I slept great.

And then when we drove across the country, Bonnie’s Dad drove a tractor-trailer, and Bonnie and I would sleep on the air mattress in the trailer, with a little door opened, and I slept so well.

Sleeping outside works really well for me.

Blister-free feet

How did you deal with the physical challenges of walking for so long? What advice would you give to individuals who aspire to undertake an extraordinary challenge such as circumnavigating the world on foot, how to do it safely and without risking health?

Definitely, wool socks! And then, you have to find shoes that figure feet well. If you find the right shoes, you shouldn’t get blisters. I tried a lot of shoes, until finding a pair that fit right – Brooks Cascadia. I would have those sent ahead, and do whatever I could to get those, because I knew I wouldn’t lose toenails, and I wouldn’t get blisters, because they just fit my feet right.

And I would say – stretch! I’d stretch every day, and if I didn’t stretch, I would feel it, for sure. You can just stretch for 5-10 minutes, that’s enough to keep you from cramping up, just to keep you moving.

Another American replaced the permanent house with constantly moving landscapes. Jessica Rambo is a single mom traveling around on a school bus!

Lessons from loss

Seven years ago, I left for a long-term journey too, and one of the motivators behind it was also reflections on life and death. I myself had some medical issues that could have been serious, luckily it didn’t turn out like that, but I was delaying the check-ups, drowning myself in the everyday grind of work. And it wasn’t until someone else in my proximity, a colleague with leukemia, experienced a life-threatening situation, that I reacted to protect myself. It made me think that I should step out of this working grind, and just remove myself from the everyday rituals to reconnect with myself. Why do you think it is that we need this type of social mirror to be able to basically act in our best interest, and take care of ourselves?

Intellectually, I think about death a lot, probably almost every night before I go to bed. And I wish I didn’t, but it’s just how it is.

A couple of months ago, my grandmother died, and I was there, just an hour before she passed. And for the week after she died, I saw the world with such clarity, and I was so much more appreciative of everything.

In a certain way, we are just dumb, and we are wired dumbly, and we just don’t see everything at once. We will fall into whatever pattern, which is good because it’s a good use of energy. You fall into some sort of rhythm and routine that works, and you are getting by, and you are surviving.

It’s not until there is a little inertia that hits you and makes you able to see and reconsider the path that you are on. And then you fall into another rut, and you are down that path, and then need another bump to help you reconsider again.

I think it’s just our wiring. If we get into a good rhythm, and if we can do something that has us surviving, then that’s probably what we will do, until something knocks us off it.

Can you tell me more about your friend Anne Marie, the person that managed to alarm your deepest questions at that crucial moment?

She was a very close friend. There were four girls and four of us guys, and we were a good close group. I grew up with her, I’ve known her since I was five years old.

She was the nicest person I knew. She was nice to the point that, when I was younger, it drove me crazy, it would just annoy me so much! “Would you just say something not nice?”, I’d ask. I could never get her to do it!

When she died, it was going from that intellectual understanding of death, to really understanding death, to seeing and feeling it. And that gave me the motivation, the alacrity, the necessity, and the feeling to do something.

The empty hollow of bucket lists

People who love to travel are often obsessed with bucket lists. They even call them “things to see before you die”. When you were faced with this idea of your mortality, I assume you mainly wanted to see the world, while you can. But do you now feel as if you have seen much more important “things to see before you die” than just crossing Machu Picchu from the list?

For me, it was never a bucket list thing. I think bucket lists are stupid, and I don’t think they get you anywhere. They could be useful in a way to motivate you and give you some direction. But the place that you go to is very rarely the thing that matters, and the thing that provides meaning to you.

Generally, you are meeting people along the way, you’re having some bad meal that has you in a bathroom for three hours, and you tell that story forever. Or you have an amazing meal at some small restaurant. Those are the places I remember.

I was at Machu Picchu, it is amazing. But I tell a thousand other stories before I would ever talk about Machu Picchu. And my memories are of a thousand other places before they’re of Machu Picchu.

When Anne Marie died, I was considering what I wanted out of life, and what I don’t. It was much more about what I wanted to experience and feel before I die, much more than where I wanted to be or what I wanted to do. It was more about the process, I wanted to understand the world and I wanted the adventure. I didn’t really care in what form that came in. These were the values I wanted to live by, and then the World Walk was just a means to achieve those values.

I think when you have a checklist or a bucket list, it’s sort of hollow. Like, ‘I wanna be a Youtuber, and I wanna go to these countries, and I’m gonna get a hundred thousand followers.’ But then you get to a hundred thousand followers and see that it doesn’t mean anything, it’s pointless.

So I think it’s much more valuable to figure out what you value. Because that will instill meaning. You can go in any direction in life. You can create any bucket list. It can be to have a big mansion, or to visit Machu Pichu, Singapore, or wherever else. But unless you know why are you doing these things, the hours you spend reaching them are just pointless.

A Canadian family decided to travel the world in order to show it to their children progressively losing sight. Meet the family of Edith Lemay and Sebastien Pelletier that follows the bucket list of things to see before going blind!

Stepping out of the rat race

Recently I talked to those TikTok Traveling Grannies that made a trip around the world in 80 days at the age of 80, which is an impressive goal for people their age. But then, on the other side of the spectrum, there is Jamie McDonald who broke a Guinness World Record by seeing the seven world wonders in less than a week. This new-age Olympics of “Faster, Higher, Stronger” is not just showing an urge for instant gratification, but also leaves an enormous carbon footprint. I know your choice of traveling on foot was formed by the financial aspect of the journey too, but can you talk a bit more about the intentional slow traveling that is a direct opposite of how people live today, travel today, and post a requested number of stories and reels on their feeds per day, so they could be “seen”?

I think it’s probably a product of a greater system in place again. You feel the need to do something voyeuristic or extreme to stand out, maybe because you have a job to get back to, or you feel like you need to make the most of this.

It’s good to step out of the system for a little bit, and realize that you will be okay. You don’t have to continue chasing down this wheel of cheese foreverTom Turcich

But I think the most valuable traveling is what the Europeans do well, getting a month off, like August, and you just go sit on the beach, or you go and wander around, and you do it slowly.

I think strangely a lot of that is more because of not having the time or not making time to travel slowly, or being afraid ‘If I quit a job, and I just go for a year, will I have a job when I get back?’ It’s a scary prospect.

But I think it’s good to, like you were saying, step out of the system for a little bit, and realize that you will be okay. You don’t have to continue chasing down this wheel of cheese forever. You can step out of it and travel slowly for a while.

I traveled in such a different way for so long that I find the quick, even a week-long trip, not very satisfying. In a certain way, it feels cheap. To get to know a place, you’ve got to be off the beaten path and talk to people that are just there.

The priceless journey

How much did this adventure around the world cost you?

I probably spent 120,000 dollars over seven years, maybe a little more than that. First two years, it was 13-14 thousand a year, I rarely went to hotels, just camped. And then there was probably 25-30 grand a year for the years after that. You can do it really cheaply if you just camp.

I had this sponsor, Philadelphia Sign, from the very beginning for the whole seven years. They gave me a baseline to rely on, and then I had my savings and started Patreon when I got to Europe, which helped a lot.

There are known corners of the world beaming with beauty, but there are also undiscovered sites, not necessarily geotagged. What was the most beautiful or awe-inspiring place you woke up to, that the rest of the world might have never seen?

Where I crossed the Andes, that’s what the children’s book is about in part, it’s called Parque Los Flamencos, it’s a very remote altiplano with some salt lakes up there and flamingos. It’s insanely beautiful, especially the Argentinian side. And then there are salt flats a little further down. That’s a really beautiful place.

There are a couple of port towns on the Peruvian coast that I wish I could remember their name. But there are a lot of little towns that I passed that are very idyllic and seem untouched. There are no tourists. When I would find these places, it was really incredible.

I’d recommend anyone to go to Kyrgistan. Very few people go to Central Asia. And even Uzbekistan which has been closed forever, is just opening up to the world. If you go to Samarkand or Bukhara, those cities are as beautiful as any cities I’ve ever been to.

Not every moment of the World Walk was all flowers and smiles. In Turkey, Tom Turcich was even held at gunpoint!

The currency of happiness

I feel you’re a true example of people doing something overwhelmingly big mainly to realize how small they are. On the other side, the smaller the bubble we live in, makes us more full of ourselves. How do you deal with your own importance today?

The primary lesson I learned is how small people are. It’s just driven on over and over again of meeting kind and intelligent people around the world who work really hard, who are in situations worse off than I am or better off than I am. I was the one walking around the world and visiting them because I had an American passport.

We’re just this minuscule little speck floating around on another minuscule little speckTom Turcich

I fell into a good job when I was younger, I was able to save money. And you just realize life isn’t all up to you, almost all of it is up to the situation that you are born into. It’s something that I struggle with.

You are so tiny. In a certain way, it’s such a relief because, you know, none of it matters. You’re just this minuscule little speck floating around on another minuscule little speck.

But on the other side, it matters a lot. Because the only currency there is – is happiness. People make money to be happy, or you want a good city design so people are happy, and you want good health care so people are happy. That’s what it all comes down to.

I see the world much more now in the way of systems than I did before. Before, I thought it was much more about world power, and personal strength. And now I get much more frustrated or inspired by good or bad systems that are helping or hurting lots of people. I don’t know if there is any emotional cost to that or the difference to it, but that’s just the change that happened over the years.

Boundaries and privilege

The US passport is the fourth on the list of the strongest passports in the world. But even you had to arrange your travels in a way that would minimize visa bureaucracy that would slow down or detour your journey. What are your final thoughts on the borders and privileges that we all come into this world with?

It’s such a complicated issue. I definitely feel very fortunate, that’s for sure. It’s country-by-country basis, it depends on the relationships with the neighbors and history.

You would think that a good, human immigration system would enable people who are intelligent and hard workers to move wherever for work and in better systems. But the system is tough.

I have a friend in Iran who has walked around Iran a dozen times, and his dream is to walk around the world, and it’s just never gonna happen. It’s just the way it is, it sucks sometimes.

As the back cover copy says, "Savannah's favorite things are smelling new places, rolling in snow, and tasty crunchy chicken wings." The children's book written by Thomas W. Turcich and illustrated by Catherine E. Turcich, follows the adventures of the first dog to walk around the world. "Savannah's World of Adventure" transports little readers to the Andes Mountains, where Savannah and her best friend Tom discover the harsh altiplano, daring llama relatives - vicuñas, and the wonderful people of Argentina. Order the paperback book based on a true dog story here.

Did you like this interview with Tom Turcich?

Pin it for later!

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning if you click on them and make a purchase, Pipeaway may make a small commission, at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our work!

I wish Tom everything the best in the world and an occupation that he will enjoy pursuing. I believe that his books will be a great success. My opinion is that there is no meaning and purpose in this life and you have to do your best to live life and enjoy it. Obsessive thoughts about death has to be treated by a good doctor, I guess.

Hi Natalia,

Thank you for your well wishes and thoughtful comment! Tom’s journey is undeniably inspiring, and his determination is truly remarkable. His books indeed hold the promise of sharing incredible stories that should captivate readers from all walks of life.

You’ve touched upon a profound aspect of existence – the search for meaning and purpose. I agree we should be all living each moment to the fullest. The topic of contemplation of mortality is a complex one, and sometimes is an essential part of deeper introspection. It is true, of course, that professional guidance can bring some peace into our reflection.

Thank you for sharing your perspective!

Very unique interview. I enjoyed a lot of different perspectives he had but my favorite line has to be “I could just do nothing and be totally satisfied.”. That is absolutely perspective at its best!

Hello Heather,

Thank you so much for your kind words! It’s wonderful to hear that you found the interview with Tom Turcich to be unique and thought-provoking.

That particular line, “I could just do nothing and be totally satisfied”, truly encapsulates the essence of finding contentment in simplicity. In our fast-paced world, Tom’s perspective serves as a refreshing reminder to appreciate the moments of stillness.

I love it when something so simple can inspire us to rethink our own approaches to life.

I wish you a lot of joy in small moments!

This gives new meaning to the feeling of emptiness that one typically feels after the vacation is over. Great interview and interesting perspectives.

Hey Michelle,

I’m glad you found the interview with Tom Turcich thought-provoking, and that it resonated with you in such a way.

The vastness of the world and the quiet moments of introspection that follow after an adventure are truly in a stark contrast.

I feel the enormous itch myself from being at one place for too long, and I think I’m gonna head for an extended adventure again to fuel my introspection with new thoughts and perspectives.

Need to fill up that emptiness 😉