If you’ve ever experienced a Chinese New Year celebration, you know it’s long, lively, and loud. But for the Hokkien people, the 9th day is the grand crescendo of the 15-day event, a festival within a festival. This is Pai Ti Kong, the Hokkien New Year, and nowhere on Earth is it longer, livelier, or louder than in Penang.

I’ve encountered some fascinating Chinese customs on this Malaysian island before, like the Valentine’s Day-esque Chap Goh Mei.

After witnessing Thailand‘s Jay Festival, I also already knew that Chinese traditions, especially when practiced outside China, tend to take on an extra level of intensity, like a cultural survival instinct.

But CNY Pai Ti Kong in George Town is a senzory overload. It’s a ceremony of cacophonic chaos, I thought to myself as I tried to decipher the event on the overcrowded streets.

Just meters apart, a priest was blessing roast pigs, costumed youngsters were dancing, and unknown firestarters created random clouds of smoke and sparkles. This is Pai Ti Kong story

I can hardly convey this confusion with words. But I could clearly read its traces in the puzzled glances of other foreigners I exchanged bewildered smiles with, while our eyebrows contorted into question marks. We all asked ourselves probably the same – What in the world is going on here?

Just meters apart, a priest was blessing roast pigs and kim chua (folded gold joss papers), costumed youngsters danced to eardrum-shattering music, and unknown firestarters created random clouds of smoke and sparkles. Some authoritative figures tried to maintain order with whistles and frantic hand gestures. It still looked improvized instead of coordinated.

I managed to dig up some details about the program at Pengkalan Weld (Weld Quay), mainly because I identified a local agency seemingly in charge of the event’s PR – Brainway Marketing. The info I got sadly offered just a provisional schedule of a brass band performance, traditional dancing, singing, drumming, and acrobatic acts. But Pai Ti Kong is so much more.

So what exactly happens on the 9th day/8th day of Chinese New Year? This is Pai Ti Kong story.

Different nations observe their calendars differently - check out how New Year celebrations differ around the world!

What is Pai Ti Kong?

Pai Ti Kong is a significant celebration among the Hokkien Chinese community. This traditional festival falls on the ninth day of the Lunar New Year (the date varies between late January and mid-February) and it is considered a second New Year for the Hokkiens.

Pai Ti Kong is dedicated to the Jade Emperor (Thien Kong), revered as the ruler of Heaven in Taoism. On this day (his birthday, in fact), he is believed to descend to earth to receive offerings made by people.

During the festival, believers express their gratitude to the deity for past blessings and seek prosperity for the coming year. In addition to grand offerings, their practice involves midnight prayers, clouds of incense, firecrackers, and fireworks.

Pai Ti Kong is seen as a day of renewal, where one seeks to start the year afresh, with not only ears ringing from all the pyrotechnics but also – good fortune.

What is the meaning of Pai Ti Kong?

The meaning of Pai Ti Kong comes from the Hokkien phrase “praying to the Heaven God”. Pai Ti Kong is a day to ask for the Jade Emperor’s divine protection.

In Chinese characters, Pai Ti Kong is written as 拜天公.

- 拜 (Pai) – means “to worship” or “to pray”

- 天 (Ti) – means “heaven” or “sky”

- 公 (Kong) – means “lord” or “deity” (referring to the Jade Emperor)

The pronunciation of the phrase can differ, depending on who is the speaker.

Pai Ti Kong in Hokkien (Min Nan Chinese) is pronounced Pài Thian Kong.

Pai Ti Kong in Mandarin (Pinyin) is pronounced Bài Tiān Gōng.

While the meaning is always the same (honoring the Great Jade Emperor, or 玉皇大帝, Yù Huáng Dà Dì), there are multiple variations in spelling and pronunciation of Pai Ti Kong. This is because of the subtle regional differences, influences of dialectal accents, and the lack of Romanization standards in Hokkien.

Pai Ti Kong or Pai Thee Kong is most commonly used by Hokkien speakers in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Singapore.

Other common variations include:

- Baai Tin Gung (Cantonese)

- Pài Tien Gong (Teochew)

- Pai Tien Kung (Hakka)

- and many other versions such as: Bai Ti Kong / Bai Ti Gong, Pai Tian Gong, Pei Ti Kong, Pai Tee Kong / Pai Tee Gong, Phai Thien Kong / Pai Thnee Kong, Pai Teen Kung

After all, Hokkien is largely a spoken language, so different spellings emerge when people try to write Pai Ti Kong in English.

Hokkien New Year history

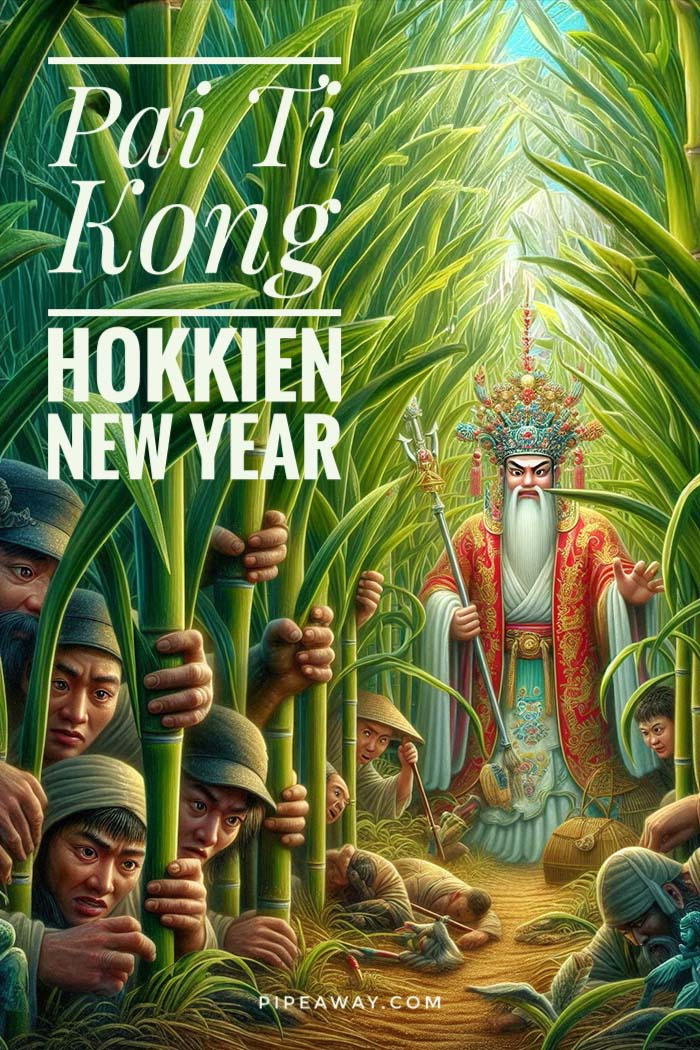

The Hokkien New Year traces its roots to the Fujian province in Southern China. Pai Ti Kong originated from a legend dating back to the Ming Dynasty, when wokou, ruthless Japanese pirates, attacked a seaside village. In other versions of the event, the attackers were debt collectors, Mongols, or even rival warlords looking to seize Hokkien lands.

Regardless of the enemy’s identity, the Hokkien people had nowhere to hide. So they sought shelter in a sugarcane field, among the towering green stalks. For eight days and nights, they survived on nothing but sugarcane’s sweet juice, while praying to their heavenly god for protection against the invaders.

On the ninth day, the enemy vanished, and the villagers came out of the plantation unharmed. Attributing their survival to the Jade Emperor’s intervention, they started the tradition of worshipping the divine protector, offering him prayers and thanks on the ninth day of the Lunar New Year. This practice has been passed through generations, eventually forming the heart of Pai Ti Kong history.

As skilled seafarers, Hokkiens migrated to various parts of Southeast Asia, bringing their customs with them. By the 17th and 18th centuries, they had established significant communities in places like Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand.

It was in these new lands that the observance of Pai Ti Kong took root and blossomed into larger, more public celebrations. Something that started practically as a family affair evolved into a vibrant Festival of Jade Emperor, complete with lion dances, dragon parades, and fireworks.

If you are interested in unusual ways to celebrate a New Year, check out the one that I spent inside Singapore Airport!

Pai Ti Kong Traditions & Rituals

Preparations for Hokkien New Year

While the Festival of the Heavenly God is celebrated on the 9th day of the Lunar New Year, in this calendar a day starts at 11 pm. So the preparations will begin already on the evening of the 8th day of the Chinese New Year.

Traditionally, people should clean their homes and set up makeshift altars – tables with red tablecloths – in front of their houses, businesses, or temples. As the king of 33 heavens, it is believed that the Jade Emperor needs open-air worship, so he can receive the prayers.

Two red candles are placed on each side of the table for divine light and protection. The altar essentials also include a censer, for inserting joss sticks after making prayers and wishes.

Some Hokkien families will wear traditional Chinese outfits for the day. Many will dress in red, as it symbolizes good fortune and attracts positive energy like a magnet.

Pai Ti Kong offerings

To please the Jade Emperor, tables are adorned with carefully arranged offerings.

Pai Ti Kong sugarcane

Probably the most essential offering of all, as it is a direct tribute to the Pai Ti Kong legend of hiding Hokkien ancestors from enemies, sugarcane (甘蔗, gān zhè) is here to symbolize protection, resilience, and sweet life.

Two stalks of sugarcane are often tied to both sides of the altar, creating a symbolic gateway for god’s arrival, and invoking protection.

Businesses also place sugarcane at their entrance, believing it will bring financial growth and success in the year ahead.

In Hokkien, sugarcane is pronounced kam chia, which sounds conveniently close to kam xia, meaning “thank you“.

Pai Ti Kong food

Food offerings to the Jade Emperor typically compose a grand birthday banquet. Once the prayers conclude, food and drinks will be shared among family and guests, ensuring everyone partakes in the blessings.

The menu typically includes:

1. Whole roasted pig

Even though the Jade Emperor is believed to be a vegetarian, his devoted followers still prepare animal sacrifices on his birthday.

Nothing screams abundance quite like an entire roasted pig sitting at the center of the Pai Ti Kong altar’s food offerings.

Back in the day, only the wealthiest families could afford to sacrifice a pig. Offering one to the Jade Emperor shows a willingness to share prosperity with the divine.

The pig must be whole (from snout to tail), as this symbolizes a complete and prosperous life. Its crispy golden skin represents cleanliness and sincerity in worship.

However, if one is not able to provide a whole roast pig to the Jade Emperor, poultry such as duck or chicken can serve as worthy substitutes. Just like the pig, these roasted birds must be presented whole, with their feet and heads intact. The same applies to whole-boiled crabs.

2. Fruits

To ensure a fruitful year ahead, it is essential to add a variety of fruits to the Pai Ti Kong table.

The pineapple is unavoidable on the Pai Ti Kong altar, as its significance goes beyond just being a tasty fruit. Its golden flesh represents wealth and luck. In Hokkien, pineapple is called ong lai (旺来), which sounds like “prosperity is coming”.

Beyond pineapples, an array of fruits is arranged at the altar, each chosen for its meaning:

Mandarins and oranges – chéng (橙) sounds like the word for “success“, and their golden hue symbolizes prosperity.

Pomelos – yòu (柚) sounds like the word for “protection” (佑), ensuring divine blessings and safety.

Apples – píng guǒ (苹果) sounds like “peace”, so the fruit promises a calm and stable year ahead.

Bananas – their curved shape is believed to pull luck toward the family.

3. Cakes

Pai Ti Kong altar is unthinkable without a selection of symbolic cakes, each carrying a deep cultural meaning. The must-have cakes are:

Huat Kueh (Huat-koé, in Hokkien) – Translating to “prosperity cake”, huat kueh (fa gao in Mandarin) is a fluffy, steamed rice flour cake that “blooms” at the top, splitting into a signature four-petal shaped crack. The word huat means “to rise” or “prosper”, making it a perfect offering for financial success, career growth, and general good fortune.

Thni Kueh (Thni-koé, in Hokkien) – This sticky, sweet glutinous rice cake, often shaped in a round mold, symbolizes a harmonious life, with good fortune “sticking” to the family. Thni kueh can have a brownish appearance, from palm sugar. Essentially the same as nian gao (“year cake”) in mainland China, this dessert is commonly referred to as kuih bakul in Malaysia.

Bee Koh (Bí-koé, in Hokkien) – Another glutinous rice cake, bee koh is a traditional Nyonya dessert popular in Penang. It is made with glutinous rice grains, coconut milk, and sugar, often flavored with pandan leaves for fragrance. In festive presentation, this pudding-style cake is steamed in a banana leaf, and infused with meanings of unity, prosperous, and stable life.

Ang Ku Kueh (Âng-ku-koé, in Hokkien) – Also known as the red tortoise cake, ang ku kueh is a glutinous rice cake, molded to resemble a turtle. The shape symbolizes longevity and endurance, the color represents good luck and happiness, and the sticky texture signifies strong family bonds. In the center of the dumpling, there’s usually a sweet filling – mung bean or peanut paste.

4. Ngor Siew Th’ng

Ngor Siew Th’ng, also known as “pink pagoda candy”, is a traditional Hokkien sweet molded into the shape of a pagoda. Made entirely of sugar, it typically comes in a bright pink color or pastel shades.

The candy symbolizes longevity, prosperity, and divine blessings.

5. Mee Suah

No birthday banquet is complete without mee suah (misua), the famous longevity noodles. These delicate, thin strands symbolize a long and smooth life ahead. Their unbroken nature represents continuous good fortune.

Typically, these wheat vermicelli are cooked in a rich chicken or pork broth and sometimes topped with hard-boiled eggs to double the luck.

Some families prefer to stir-fry the noodles with mushrooms and dried shrimp, adding extra layers of umami.

For an additional boost of blessings, elders may insist that you slurp the noodles without biting them, ensuring uninterrupted longevity.

6. Eggs

Eggs may seem like a humble offering, but in the context of Pai Ti Kong, they hold deep symbolic meaning. They represent fertility, renewal, completeness, and the cycle of life.

The most common variation is red-dyed hard-boiled eggs, where the color symbolizes joy, blessings, and protection.

7. Drinks

Besides food, a grand banquet needs a drink to toast the respected guest of honor, in this case – the Jade Emperor.

Rice wine is normally offered in small cups as a way of celebrating and showing sincerity.

Tea (usually oolong or pu’er tea) symbolizes purity and respect.

Some families also serve sugarcane juice, directly referring to the Pai Ti Kong legend, and reinforcing the idea of sweet survival and a smooth year ahead.

Flower offering for Pai Ti Kong

Offering flowers is an integral part of Pai Ti Kong rituals, symbolizing purity, respect, and good fortune.

The Five Types of Flowers Offering (五色花供, ng se hu in Hokkien) is a traditional floral arrangement presented to the Jade Emperor as part of the grand ceremony. Each type of flower carries a specific meaning, representing different aspects of blessings.

While flower types can vary, the traditional five include chrysanthemum (long life and resilience), lotus (purity and wisdom), peony (business success and financial stability), orchid (love and harmony), and plum blossom (endurance and new beginnings).

Paper offerings at Pai Ti Kong

In Chinese folk beliefs, material wealth exists in both the earthly and spiritual realms. Pai Ti Kong bridges these worlds by having devotees burn paper representations of valuables. The practice is rooted in their hope for a transaction – exchanging paper gifts for blessings.

Pai Ti Kong paper offerings can come in various forms:

– gold and silver joss paper (jīn zhǐ & yín zhǐ) – gold for deities, silver for celestial beings, it represents wealth and prosperity

– gold ingots (yuán bǎo) – stacks of boat-shaped ingots made of joss paper can form large pyramid-shaped towers, representing financial achievement and fortune

– heaven money (tiān jīn) – paper currency, sometimes with printed images of the Jade Emperor, serves as a symbolic tax to the celestial world; some devotees write their names and wishes on the notes before burning them in bundles

– other paper goods – some families create paper clothing designed for heavenly beings, or paper replicas of luxury homes, cars, yachts, smartphones, and even servants, all meant to provide a comfortable afterlife for divine figures

Paper offerings are burned in order, from smaller to larger items. The belief is simple: the bigger the offering, the greater the blessings in return!

Some devotees toss long sugarcane stalks into the fire as an extra offering, watching as the smoke carries their prayers to the heavens.

Fake money ends up in flames at Songkran in Cambodia too. Here's what to know about the Khmer New Year!

Pai Ti Kong prayers

During Pai Ti Kong, devotees recite prayers to express gratitude and seek blessings from the Jade Emperor.

The Pai Ti Kong prayer process begins with lighting long joss sticks, a symbol of communication with the heavens. Worshippers bow three times before placing joss sticks into the altar urn. They silently say thanksgiving prayers and mantras.

While some follow structured prayer texts, others simply offer their heartfelt words. In general, prayer includes an offer of gratitude for the past year’s protection, and expressing new wishes for the coming year – for good health, happiness, prosperity, and peace for the prayer’s family.

Pai Ti Kong wishes can then enter an area of personal aspirations and could include career success, wealth attraction, academic achievements, longevity, and a fulfilling life.

At the end of the prayer session, devotees clap their hands together or raise them to the sky while shouting the Hokkien prosperity chant three times: “Huat Ah! Huat Ah! Huat Ah!” (meaning: “Prosper! Prosper! Prosper!”)

Once prayers are completed, devotees burn gold paper money and symbolic items as an offering to Ti Kong and the heavenly realm.

Pai Ti Kong fireworks

What begins as a small ceremonial blaze at the altar escalates into a grand spectacle above – the fireworks. During Pai Ti Kong, skies explode in a riot of colors, noise, and light, in a very celebratory reverence for the Jade Emperor. It is believed these little rockets will carry prayers and gratitude to the heavens.

In Hokkien tradition, firecrackers are also a way to express welcome to Ti Kong. And the rule is: the louder, the better. Long chains of red firecrackers are set off in rapid succession, believed to chase away bad luck and evil spirits and secure a year of abundance ahead.

Lion and Dragon Dance for the heavenly god

Followed by thunderous beats of drums and clashing of cymbals, traditional performances such as lion and dragon dance are a living tribute to the Jade Emperor.

These performing troupes visit homes, shops, and temples, with leaping lions and flying dragons bringing fortune and protection.

In places like Penang, the grand street parade will see multiple performances of these animated animals, infusing the Pai Ti Kong event with energy and communal pride.

Where is Pai Ti Kong celebrated?

While Pai Ti Kong’s origins lie in Fujian, the Chinese regions of Xiamen, Quanzhou, and Zhangzhou uphold the tradition today with temple processions and massive communal feasts.

However, the festival is widely observed in Hokkien communities around the world. It has taken on a life of its own in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Taiwan, and other diaspora hubs (Bangkok, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Sydney).

Malaysia hosts some of the most lavish Pai Ti Kong celebrations outside of China. One can witness these events in Kuala Lumpur (Petaling Street – Chinatown, and Klang) and Johor Bahru, but the undisputed epicenter of the Pai Thnee Kong celebration in Malaysia is Penang.

The most important island temples during Pai Ti Kong are Kuan Yin Teng or Goddess of Mercy Temple on Jalan Masjid Kapitan Keling, and Thean Kong Thnuah Temple, also known as the Jade Emperor’s Pavilion, in Ayer Itam (not far from Kek Lok Si Temple).

In George Town, streets around Weld Quay, especially next to Chew Jetty and other Clan Jetties, come alive with massive altars, lion dances, and sky-filling fireworks.

During Pai Ti Kong in Penang, road closures are implemented to accommodate the influx of visitors, as well as performances and rituals taking place in the street. Typically, there are phased road closures around the Pengkalan Weld area. The part between Gat Lebuh Chulia and Gat Lebuh Acheh closes for the entire day, while other streets join in the afternoon. Follow official announcements for real-time updates!

When is Pai Ti Kong?

Pai Ti Kong follows the Chinese calendar, always falling on the ninth day of the first lunar month. This means that, in the Gregorian calendar, Pai Ti Kong date shifts each year.

Below are some upcoming Pai Ti Kong days:

🏮 2026 – January 25 (Wednesday)

🏮 2027 – February 14 (Sunday)

🏮 2028 – February 3 (Thursday)

🏮 2029 – February 11 (Sunday)

🏮 2030 – February 11 (Monday)

While Pai Ti Kong officially falls on the ninth day, beware that devotees begin their prayers at night of the eighth day, so if you want to experience loud firecrackers, lion dances, and massive feasts, plan to arrive a day earlier.

Where to stay in Penang during the Hokkien New Year?

A popular place to stay in Geroge Town during Pai Ti Kong is the Seven Terraces Hotel. This restored heritage mansion is just a 5-minute walk from the Goddess of Mercy Temple, but more importantly, the hotel hosts a traditional dragon dance at its premises during the festival, offering guests an immersive experience. Compare prices for your dates on Booking, Agoda, or Trip.

For mid-range comfort, you can check out Muntri Mews, a stylish heritage hotel with spacious rooms, a café downstairs, and a quiet lane for relaxation. Find the best price for your date on Booking or Trip.

Another solid option is Areca Hotel Penang, a family-friendly heritage hotel with great service, located near Komtar for easy access to different areas. You’ll find the perfect rate on Booking, Agoda, or Trip.

If you don’t need deluxe amenities, a price-friendly option in the neighborhood is a cozy Li’s Inn. Room prices start below 20 euros already. For the best rates, check Booking or Agoda.

Pai Ti Kong in Penang – Conclusion

With car traffic banned during the Pai Ti Kong holiday, the road alongside the Clan Jetties in George Town becomes a grand pedestrian promenade.

If you get there earlier, you’ll be able to enjoy a relaxed stroll between giant joss sticks decorated with dragons, playful dancing mascots, and food stalls offering everything from boiled eggs and skewered meat to Turkish coffee brewed in the sand.

But once the program kicks off, especially after 8 p.m., expect a pedestrian traffic jam as the crowds pour in. You can relive the Pai Ti Kong atmosphere in our Pipeaway Walks video, giving you a glimpse of the joyful chaos.

Pai Ti Kong allows us to come together in a cheerful spirit that postpones tomorrow

There is an informal competition between Clan Jetties, trying to overshadow each other with artistic programs and extravagant altar set-ups. With so much happening at once, even the local security forces have a dubious success rate while trying to maintain order.

When the firecrackers and fireworks take over, the crowded streets magically clear up in explosive circles. People might be on top of each other already but don’t underestimate what some unexpected spark can do for opening up the space.

Hokkien Pai Ti Kong is a celebration that can last until 4 a.m., with locals who have to work the next day grumbling about the uncontrolled noise this night produces, especially in the context of the ongoing Chinese New Year celebrations. Long, lively, and loud.

Pai Ti Kong tradition in Penang is one of the strongest in the world. It allows Hokkiens and the rest of us to come together in a cheerful spirit that postpones tomorrow.

Happy New Year, happy Pai Ti Kong!

How do you like Pai Ti Kong? Would you like to celebrate the Hokkien New Year in Penang?

Pin this guide for later!

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning if you click on them and make a purchase, Pipeaway may make a small commission, at no additional cost to you. Thank you for supporting our work! The authors of all photographs are mentioned in image titles and Alt Text descriptions. In order of appearance, these are: Photos with odd numbers (1, 3, 5, 7, 9) - nicholaschan, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Photos with even numbers (4, 6, 8) - Ivan Kralj AI images (2, and pin image - 10) - Ivan Kralj - Dall-e/Adobe

It sounds like this is a great time to experience the culture but also to explore Penang Island without the cars in this area.

You’re absolutely right, Sonia!

Pai Ti Kong is the perfect time to soak in Penang’s vibrant Hokkien culture and enjoy a rare car-free stroll around the Clan Jetties.

Just be prepared for some “pedestrian traffic jams” once the celebrations kick into full swing!

I love hearing about how other cultures celebrate the holidays.

Every culture has its own unique way of celebrating, and Pai Ti Kong is a spectacular mix of gratitude, food, fireworks, and traditions passed down for generations.

Glad you enjoyed learning about it, Amy!